At the Core of the City

The dispersed Chinese population who can often meet their cultural and religious needs closer to home in the suburbs is one challenge facing Calgary Chinatown today. In 2016 less than 2% of the city’s total Chinese population lived in Chinatown.

President of the Jiang Zhe Shanghai Association, Mr. Yuan Tao Di (right) hands out fresh bread during a dance event at a community hall in Chinatown. Since the mid-1990s, strong emigration of Mandarin-speakers from mainland China and other Chinese diaspora around the world have outweighed the first waves of Cantonese-speaking immigrants from Hong Kong. As a result, many associations and organizations now offer services in Mandarin.

Everyday, Mr. and Ms. Fok play mahjong in their condo apartment located in Chinatown. Married in 1950 in Hong Kong, they retired and immigrated to Calgary in the early 1990s. Many Chinese immigrants choose Canada for its overall quality of life. In 2018, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) annual survey ranked Calgary fourth on their list of the world’s most livable cities.

Often 3rd and 4th generation Chinese-Canadians have no direct tie with China other than the cultural heritage their ancestors maintained within their family tradition and within Chinatown.

In the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, Chinatown entered a revitalizing stage. Money from local and international investors helped build numerous residential and commercial projects such as the Dragon City Mall. Upon completion in 1994 it was the largest Chinese mall in Canada.

The Calgary Chinese community continues to grow and is one of the most deeply-rooted visible minority groups in the city. In 2016 the population of Calgarians of Chinese ethnic origin was 104 000.

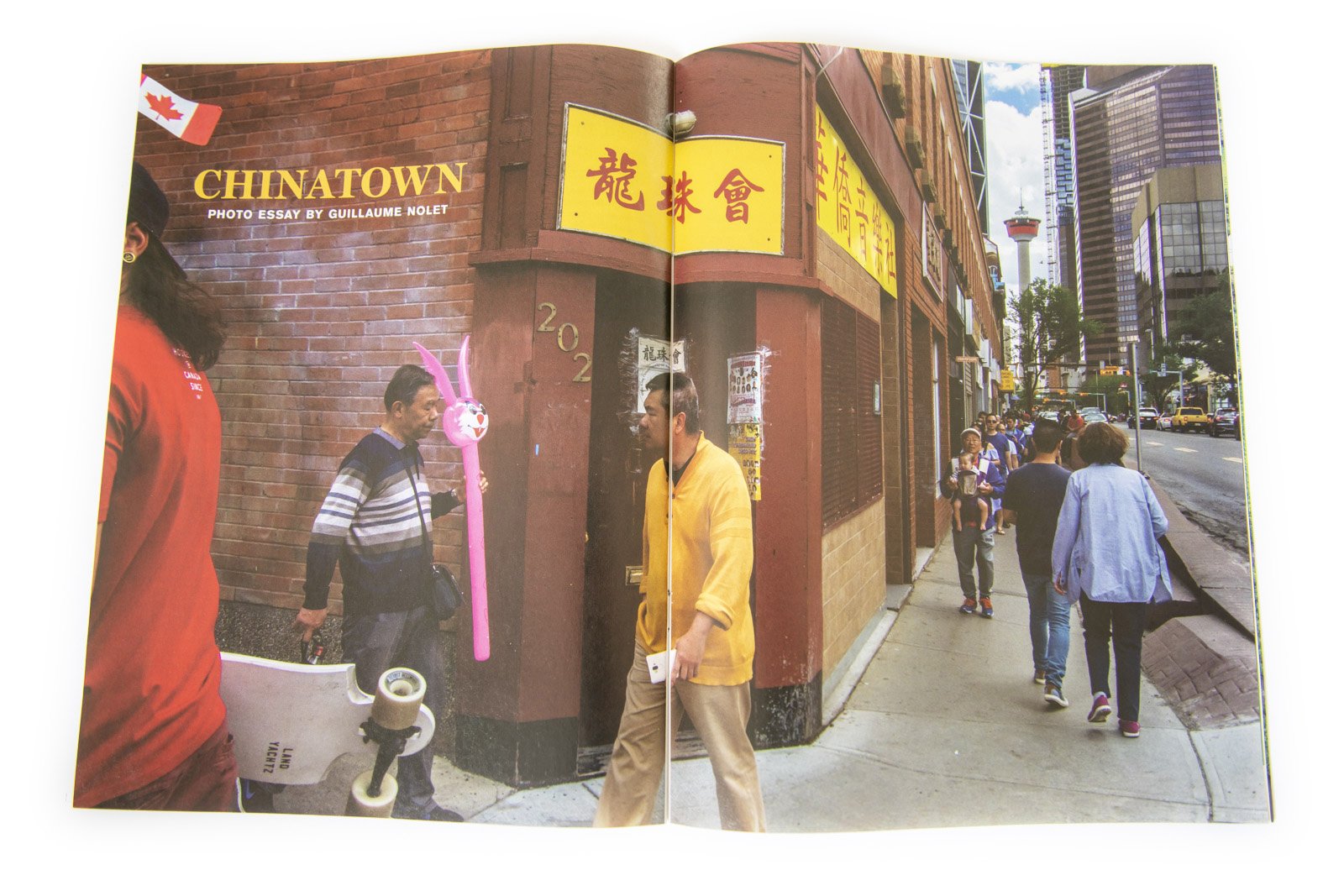

Crowds flock to Chinatown in Calgary on Canada Day. The city’s Chinatown has been relocated twice- first in 1886 after a fire on Stephen Avenue destroyed half of the neighbourhood, and again in 1910 when a Canadian Pacific Railway proposal to build a hotel in the vicinity of Chinatown forced residents to relocate. Since then, Chinatown has remained in its present location on the North side of downtown.

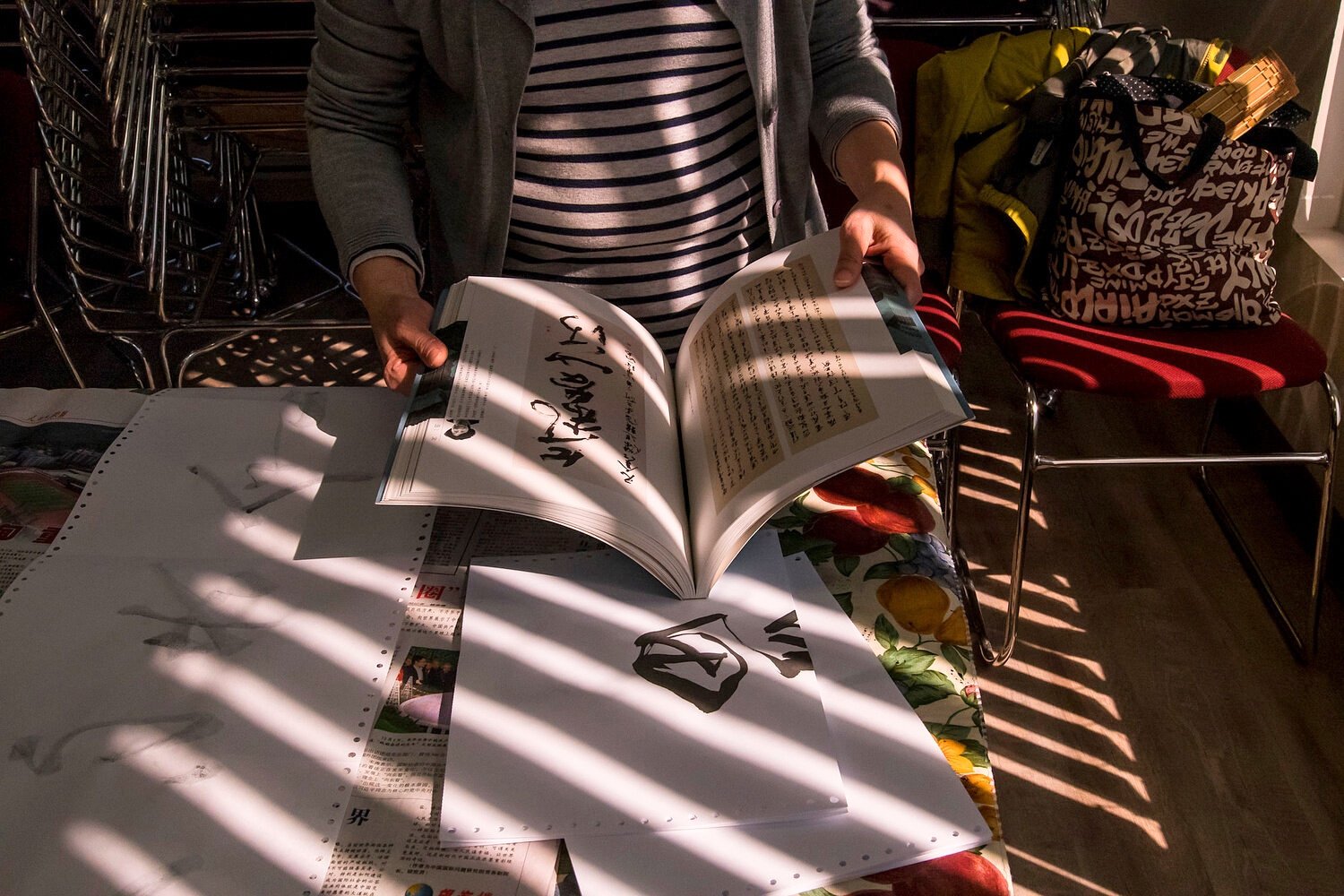

Chinese calligraphy class in Calgary Chinatown.

A group of young volunteer removes graffitis during a clean-up day in Chinatown. In recent years members of the community have made considerable efforts to revitalize the neighbourhood.

In 1923 the Chinese exclusion law was introduced and prevented Chinese from immigrating into the country. Many young men were separated from their wives and families until the law was repealed in 1947. Even if the attitude towards Chinese changed shortly after WWII, it was not until 1967 that Chinese received “Equal Rights” and were admitted in Canada under the same criteria as people of other origin.

Young violin players gather to perform at the Calgary Chinese Cultural Centre. With a substantial number of middle-class families coming to Canada from Mainland China, parents can afford and push for early musical training.

James Yee checks his son’s guitar before his performance of Bohemian Rhapsody by Queen during a family event. The young generation of Chinese Canadians are increasingly exposed and influenced by western culture. Therefore, more young Chinese study western instruments like guitar, piano and violin rather than traditional instruments.

Japanese dancers prepare before performing at the Chinese Street Festival in Calgary. Chinatown helps different Asian associations to work together in promoting cultural diversity; a sentiment not always echoed in the past, especially during WWII when Sino-Nippon relations were at their worst.

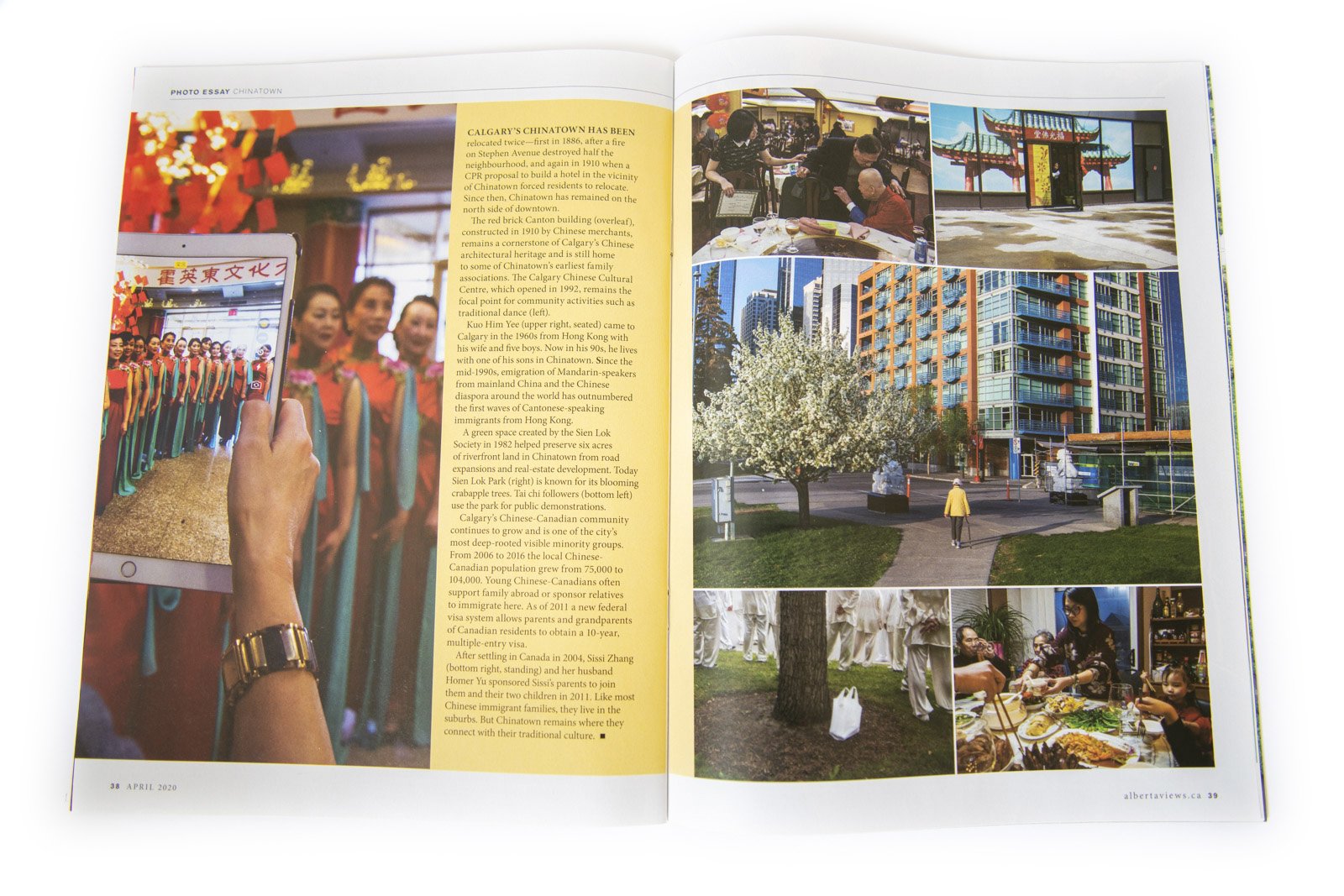

Traditional dancers pose for a portrait at the Calgary Chinese Cultural Centre.

This parking lot on the eastern side of Chinatown is a proposed site for a $350 million commercial and residential project. Many residents and members of the community fear the controversial 28-storey, three-building development. They believe it will jeopardize and weaken the cultural and heritage fabric of Chinatown. Rapid-city redevelopment and accelerated gentrification have been recurrent threats for the century-old Chinatown community.

Young Chinese-Canadians often support family abroad or sponsor relatives to immigrate here. As of 2011 a new federal visa system allows parents and grandparents of Canadian residents a 10-year, multiple-entry visa. After settling in Canada in 2004, Sissi Zhang (centre) and her husband Homer Yu sponsored Sissi’s parents to come join them and their two children in 2011. Like many Chinese immigrant families, the Yus live in Calgary’s suburbs, where homes cost less, making visits to Chinatown less frequent.

A chef makes noodles at one of Chinatown’s oldest and most known restaurant: The Silver Dragon.

Women get ready backstage before a performance during a Chinese New Year concert at the Calgary Chinese Cultural Centre.

Members from the Yee Fung Toy Society poses for a portrait during a New Year celebration event. Several traditional clans composed of members with the same family name were established in Chinatown during the first quarter of the 20th century; like the Calgary chapter of the Yee Fung Toy Society created in 1920. Originally to assist with personal and community welfare services, such as employment and lodging, these century-old organizations also helped members manage prejudice, discrimination and racism prevalent at the time. Today, clan associations fulfill fewer functions but still remain a crucial and important part of building a sense of belonging and togetherness within the community.

Kuo Him Yee (right) immigrated to Calgary in the 1960s from Hong Kong with his wife and five boys. Now in his 90s, he lives with one of his sons in Chinatown and has remained a member of the Yee Fung Toy Society since 1964.

Teenagers embrace on the shore of the Bow River. As a riverfront community steps away from downtown, Chinatown is a prime real-estate location highly sought after by condo developers.

Late afternoon light outlines the two-storey red brick Canton building. Constructed in 1910 by Chinese merchants, it remains a cornerstone of Calgary’s Chinese architectural heritage and is still home to some of Chinatown’s earliest family associations. It is a reminder of the hard work and determination of the first Chinese-Canadians who helped build this city.

The early-morning light outlines the blooming crabapple trees in Sien Lok Park. This green space built by the Sien Lok Society in 1982 helped preserve six acres of riverfront land in Chinatown from road expansions and real-estate development.

In 2016, almost one in three Calgarian was a first generation immigrant. Strong immigration from the Philippines and India in recent years as outweighed China has the number one newcomer group to Canada. The Chinese-Canadian population remains however considerably important in all large Canadian cities.

For many Chinese-Canadians, the neighbourhood is where they connect with their traditional culture. Being one of the most walkable districts in Calgary, Chinatown is steps away from restaurants, stores, public transportation and multiple landmarks such as Sien Lok Park, Eau Claire Market and Prince’s Island.

Despite a growing elderly population, accelerated gentrification and the suburbanization of the Chinese population, Calgary’s Chinatown will have to evolve and adapt like it has done for more than a century in order to stay relevant.

A Canada goose rests in front of a mural in an alleyway in Chinatown. The wall commemorates the family names of early Chinese-Canadians who came to Calgary at the beginning of the 20th century to work hard with a hope of finding a better life. Despite facing decades of racism, hostility and isolation, they succeeded at building a resilient Chinatown that is still standing today and has become a cultural landmark of Alberta’s history.

At the Core of the City: Chinatown

Calgary’s Chinese community was established when immigrants from China arrived to labour on the railroad at the end of the 19th century. In its 135 years history, Calgary’s Chinatowns have been facing constant threats of disappearance. Today, rapid city redevelopments and accelerated gentrification are reasons why Chinatown is at risk. This is happening even as new economic prosperity in China is allowing new immigrants to settle in Canada.

Despite facing other challenges such as a growing elderly population and the increasing suburbanization of the Asian population, Calgary’s Chinatown will evolve and adapt in order to stay relevant.

Chinese Canadians have a deep emotional and personal attachment for this neighbourhood. This Chinatown is one of many immigrant communities across Canada who played a historical role in helping build this nation and still continues to shape the cultural landscape of today. Many similar neighbourhoods in North America are fighting for their survival. These images are an homage to it’s preservation.